But there’s one myth which has been more effective and more pervasive than any of these—the long tailpipe theory.

The long tailpipe theory is everywhere. Anyone who doesn’t like EVs points it out immediately. So what’s the theory? I’ll let Fox News’ Greg Gutfeld do the honors:

“The entire reason for doing these stupid little cars is a lie because electricity comes from coal. In some cases, some studies show that these can produce more pollution than internal combustion engines.”40

Upon first examination, this makes sense. Let’s bring back our US emissions chart to see what Greg means:

US Emissions 2013 2

Earlier in the post, we identified the two biggest causes of CO2 emissions: cars running on gas and coal making electricity. The long tailpipe theory’s logic is that all an EV does is shift energy production from the first bad category to the second bad category. Since coal is the most prominent source of electricity in the world, and coal emits about 1.5 times more carbon than oil per joule of energy produced, EVs are actually worse emissions culprits than gas cars.

When you read about EVs or talk to people about them, you’ll hear this theory come up again and again and again and again.

The thing you’ll notice, though, is that every time you hear someone all mad about the long tailpipe emissions of EVs, they’re using wording like, “may be” and “often” and, in the case of Greg, “in some cases, some studies show.” That’s because you have to use words like that when you’re saying things that you wish were true but actually aren’t.

Taking the US as an example, here’s why they’re wrong:

1) US electricity production is mixed, not just coal. Coal only makes up 39% of US electricity production. And that number’s going down:41

Natural gas, which emits less than half the CO2 of coal, now makes up over a quarter of US electricity production. Nuclear and renewables emit almost no CO2 and now produce a third of US electricity.

2) Energy production is more efficient in a power plant than it is in a car engine. To use an example with an identical source fuel, burning natural gas in a power plant is about 60% efficient, meaning 40% of the energy of the fuel is lost in the energy production process. In a car, burning gas is less than 25% efficient, with the vast majority of the energy lost to heat. The larger more complex system at a power plant will always be far better at capturing waste heat than a tiny car engine. The increased efficiency means that even a car running purely on coal-generated electricity will emit carbon at the same rate as a gas car that gets 30 miles per gallon—which would be a significantly cleaner-than-average gas car.

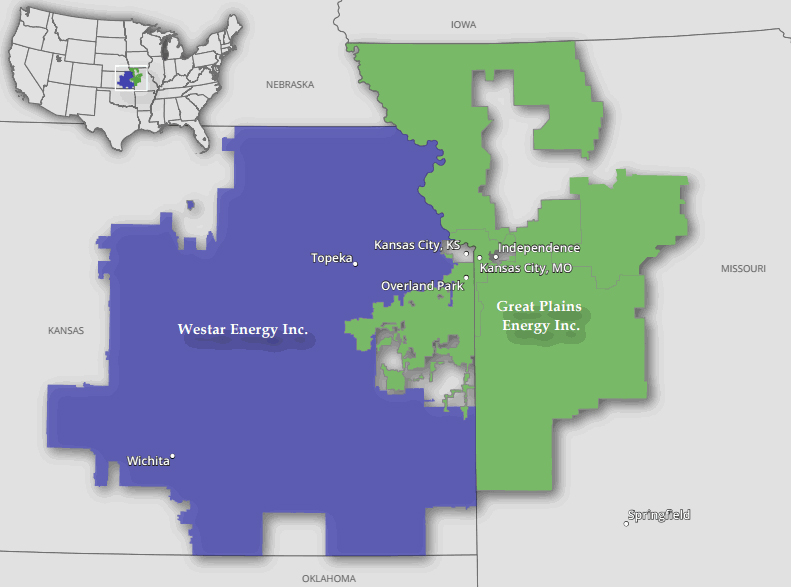

Because the breakdown of energy source is different in different states, an EV will be greener in some places than others. The US Department of Energy has a great tool to assess exactly how an EV stacks up against a gas car in any zip code in the country.

In the parts of the country that use very little coal, like upstate New York, an EV’s well-to-wheel emissions are far less than that of a gas car (on the chart, HEV = a traditional hybrid car, PHEV = a plug-in hybrid car):

In the heaviest coal states, like Colorado, EVs cause a lot more CO2 emissions—but still less than a gas car:

The national average is somewhere in between, putting an EV at 61% of a gas car’s emissions overall:

The Union of Concerned Scientists came up with a way to directly compare car emissions, regardless of the type of car it is—a metric called “miles per gallon equivalent,” or MPGghg (ghg stands for greenhouse gases).

MPGghg is how many miles per gallon a gas car would need to achieve in order to match the carbon emissions of an EV (in the EV’s case, the emissions come from the plant that makes the electricity). In other words, if an EV gets 40 MPGghg, it means it emits the exact same amount of carbon as a gas car that gets 40 MPG.

The average new gas car gets 23 MPG. Anything above 30 MPG is really good for a gas car, and anything below 15 or 17 is bad. For reference, remember that an EV running on just coal-produced electricity would have an MPGghg of 30 (so even in a hypothetical entirely coal-powered state, an EV would be the same as a highly efficient gas car), and an EV running on just natural gas-powered electricity would have an MPGghg of 54 and just top the Toyota Prius, which runs at 50 MPG.

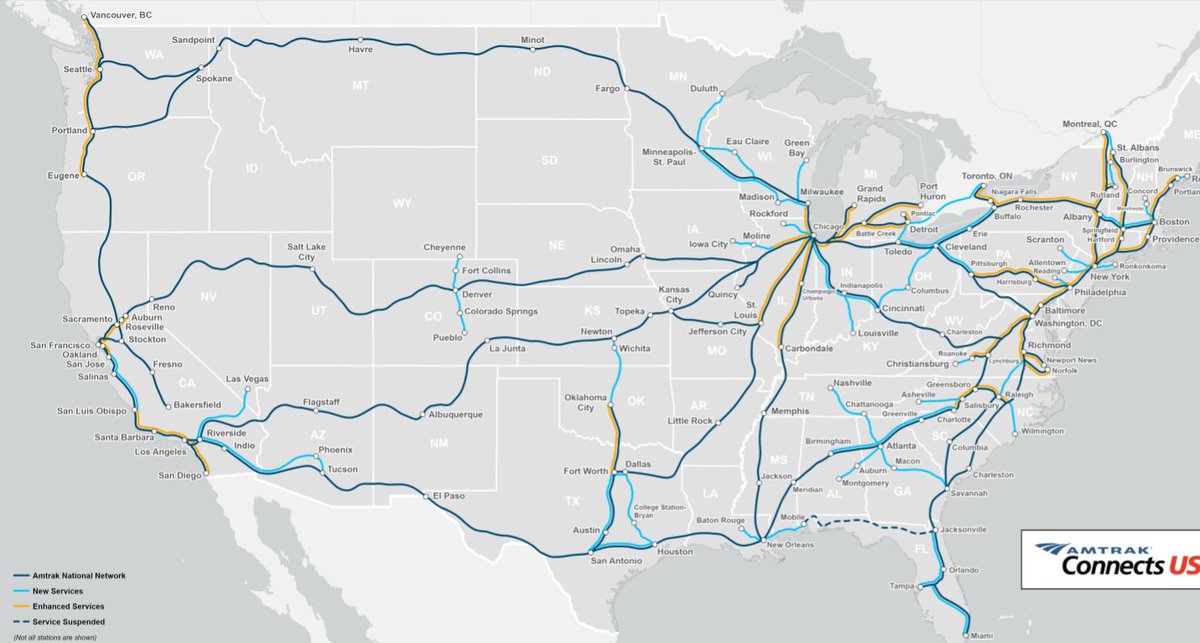

Here’s a useful map that shows the kind of MPGghg EVs get in different parts of the US:42

MPG Map

So even for the 17% of the population living in the worst coal states, an EV beats almost all gas cars. This sums it up:43

And the thing is, each year, that already-nicely-positioned blue bar will make a little jump to the right. Because the grid is getting cleaner every year, it means an EV gets cleaner as time goes by. Gas cars are locked where they are, and they’ll be stuck watching as the future pulls away from them.

___________

I didn’t feel strongly about this topic before I spent a lot of recent time learning about it—and now that I have, I kind of think the only way someone could feel positive about a gas car future is if they’re misinformed, personally financially interested in gas cars, hopelessly old-fashioned, drunk with politics, or kind of just being a dick? Right? They would have to be one of those five things to be super pro-gas car—right?

The battle going on isn’t about gas cars vs. electric cars. That one’s already decided. This is a war about time. Oil companies will try to slow things down, and they may succeed—but they’re not winning this one. I just don’t see how they could. A company that makes lantern fuel can stay strong for a while by shielding the public from understanding what a light bulb is, but eventually, people will figure it out and lanterns will be out of business, bringing the lantern fuel company down with it. Greasy hoods are old, noisy acceleration is old, overheating engines are old, oil changes are old, and it won’t be long before everyone realizes that. A fun field trip in 2050 will be taking your grandkid to see an old 20th-century gas station and explaining how it worked.25 Driving a gas car is like littering on a camping trail, smoking on an airplane, and throwing a big stack of paper in the trash, and it’s just a matter of time until public disgust catches up to it.